The Leicaflex Saga: The Agony and Ecstasy of Creating Leica’s first SLR.

It has its charms, and it can take great pictures, but it sure didn’t sell!

By Jason Schneider

Peter Karbe, Portrait by Alan Weinshel

The introduction of the Nikon F in 1959 changed everything. Within a few years Nikon, and other Japanese camera companies, released innovative products that positioned, and eventually solidified, the 35mm SLR as the new professional standard, upending the longtime supremacy of 35mm rangefinder cameras. Even the glorious Leica M3 and M2 couldn’t compete in terms of optical flexibility or framing accuracy, especially when shooting at close distances or with telephotos or very short wide-angle lenses. Significantly, seeing buyers snap up SLRs, Nikon went all in on the Nikon F (which remained in production for 14 years until 1971!), discontinuing such esteemed rangefinder classics as the Nikon SP, S3, and S4 by 1960.

Of course, the Germans weren’t exactly sitting on their hands. Indeed, most photo historians credit the Dresden-made Kine Exakta of 1936 as the world’s first mass produced, widely distributed 35mm SLR. And after WW II the ranks of German-made 35mm SLRs expanded to include the Edixa made in Wiesbaden, the elegant DDR-made Contax S and (from 1959 to 1966) the large, heavy, exquisitely made, but overly complex Zeiss-Ikon Contarex line assembled in Stuttgart

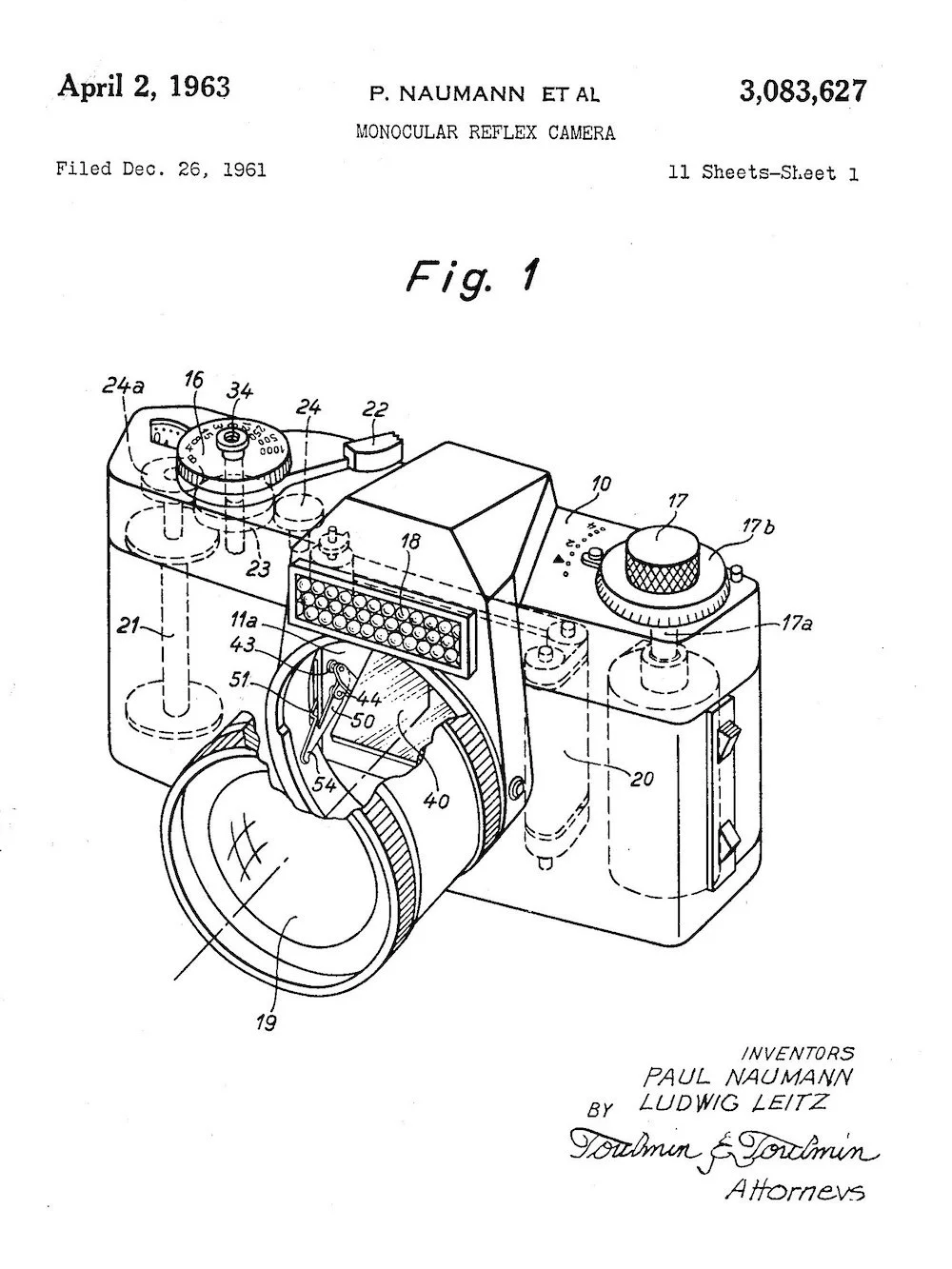

Leitz Wetzlar was, of course, painfully aware of these cataclysmic changes, and at least some of its top management realized it would have to develop a creditable Leica SLR if it expected to survive in a changed marketplace. By the early ’60’s the engineering department had hand built several attractive prototypes of what a future “Leicaflex” might look like, and what features it would include. One had a prism with a selenium meter grid built into its front. Others had top-mounted accessories and/or interchangeable prisms that could theoretically include a TTL meter like the prisms offered for the Nikon F. One component found on prototype Leica SLRs that did eventually wind up on the production Leicaflex I (retrospectively known as the Leicaflex Standard) was the new R- (for “reflex”?) bayonet mount, which has an internal (throat) diameter of 57.8mm. This is noticeably larger than the 44mm throat diameter of the Nikon F-mount, thereby enhancing the Leicaflex’s optical flexibility.

Regrettably, all this inspired effort and dedication culminated in a technological whimper, the original Leicaflex I or Standard. Officially released in 1964, it’s a beautifully made, ultra-conservative camera with a fixed prism and non-TTL metering, and as such it had little chance of successfully competing in the vibrant, rapidly evolving 35mm SLR marketplace. In production from 1964 to 1968 only 37,500 units were made, compared to about 70,000 units for the Leicaflex SL of 1968 to 1974, which was more advanced and included selective center-weighted metering. Even that turned out to be too little, too late as Leica was playing catch-up with the Japanese competition.

How could Leitz, a company renowned for its technological prowess and unsurpassed manufacturing excellence, come up with what can charitably be described as a pedestrian 35mm SLR? Some experts have conjectured that Wetzlar was too focused on competing with its archrival Zeiss Ikon and its ponderous “Bullseye” Contarex rather than on creating a German equivalent of the Nikon F, a far better, less complicated design that could be produced at far lower cost. Leica historian James Lager, who was certainly positioned to know, says that the technical gurus at Leitz steadfastly rejected the idea of an SLR with interchangeable finders and screens because they were fixated on the (overblown) possibilities of misalignment, and dust intrusion when swapping finders and screens.

So, what are the foibles of the first Leicaflex? For one thing it lacks a through-the-lens light meter. On the front of the meter prism, next to the round battery cover, there’s a small, framed window for the external CdS meter cell. The camera also lacks both an interchangeable prism and the ability to attach a motor drive, dashing any hopes of it being adopted by large numbers of pros and sports/action shooters. And its long-stroke non-ratcheted wind lever is not great for rapid firing. It was also very expensive when released in ‘64--$585 with 50mm f/2 Summicron-R lens, equivalent to $5,210.45 in 2025 dollars! Despite the high price it was so fastidiously overbuilt that Leitz is said to have lost money on every Leicaflex sold, though this has never been officially confirmed. Does this beast have any redeeming virtues? You bet. It has a nice big grippable shutter speed dial that provides a top speed of 1/2000 sec, its shutter fires smoothly with a reassuring sound, the meter is accurate if you know how to use it correctly, and it’s capable of capturing outstanding on-film results with any of its superlative R-mount lenses.

When you bring a Leicaflex Standard up to your eye and observe the large, bright non-focusing image with a smallish circular (microprism) focusing area in the center of the field, perhaps you’ll understand why none other than James Lager affectionately refers to it as “a Leica M3 fitted with a Visoflex reflex housing and surmounted with a coupled Leica MR meter.” In other words, the Leicaflex is a rangefinder camera at heart, and it shows what happens when the greatest rangefinder camera company in the world was compelled by competition to create its very first SLR.

You can snag a clean Leicaflex I (Standard) body in black or chrome online for about $125 to $200. One with a 50mm f/2 Summicron-R lens will set you back around $500. Profuse thanks to James Lager for providing all the images for this article.