DR. WOLFF’S TIME HAS COME: THE DR. PAUL WOLFF & TRITSCHLER STUDIES

In 1999, LHSA published a special supplement to Viewfinder (Vol. 32, No. 4) entitled “Dr. Paul Wolff, Pioneer of Leica Photography”. This supplement was the brainchild of then-president of LHSA Roy Moss, together with Dr.Cyril T. Blood of the British LHS and this reviewer, and included several articles plus a partial bibliography of Dr. Wolff ’s books. Roy felt that Dr. Wolff was an important Leica pioneer and teacher whose reputation had somehow waned and needed new emphasis, and both Cyril and this reviewer had been amassing bibliographic data on Dr. Wolff, and shared Roy’s feelings. Other LHSA members who expressed their interest and contributed writings to the supplement included Joe Brown, Will Wright, and Bill Rosauer.

In our introduction, Cyril and this reviewer expressed the opinion (actually more of a hope) that what we were doing in promoting Dr. Wolff ’s photography would lead to something larger. That prophesy appears to have been at least somewhat correct, now twenty years on. A major book on Dr. Wolff has just been published, with an associated exhibition at Leitz Park in late June, 2019. There is at least one Ph.D. thesis being written on Dr. Wolff currently as well.

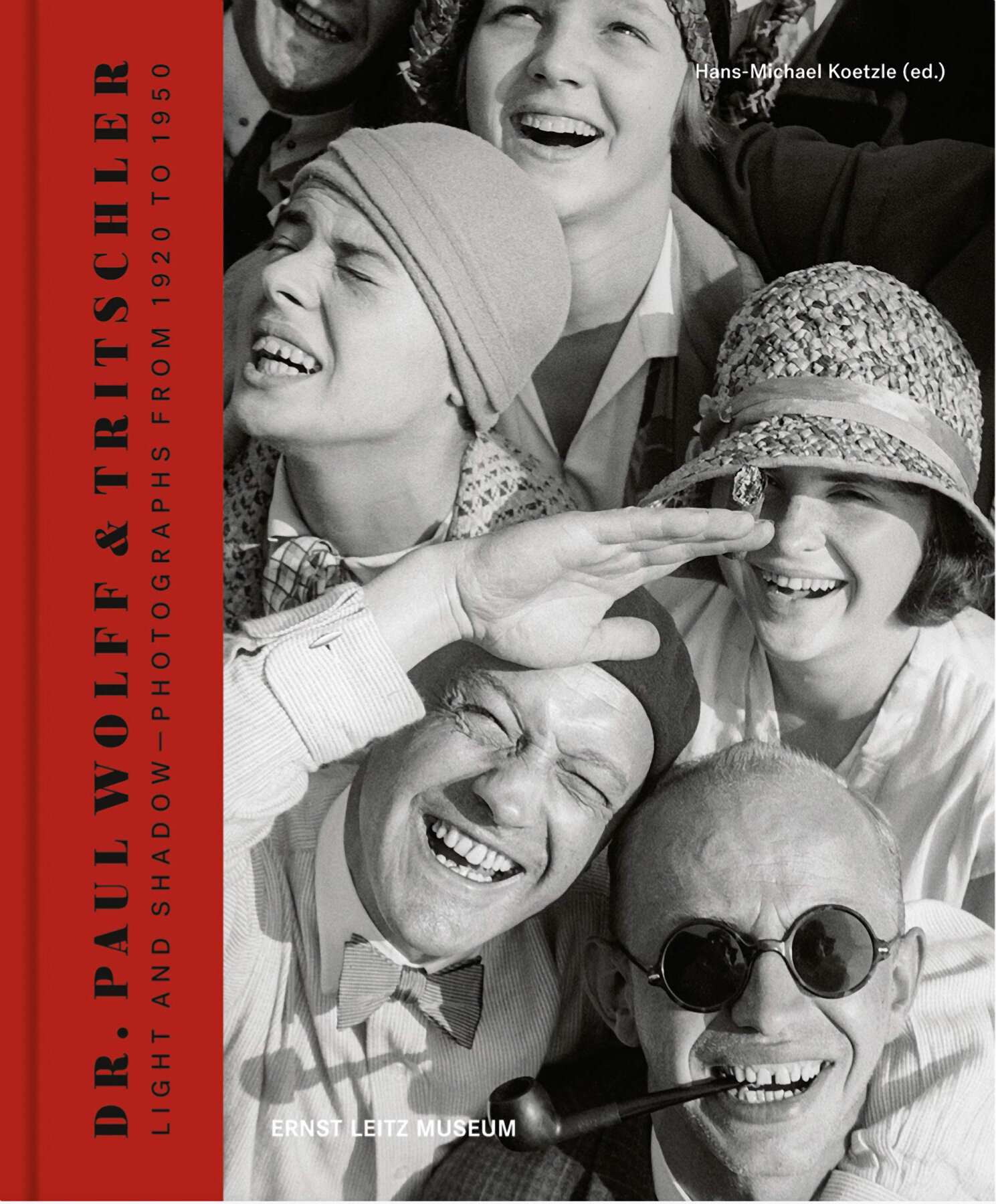

That book is Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler: Light and Shadow

– Photographs from 1920 to 1950 [German Edition Paul Wolff & Tritschler – Licht und Schatten], Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, edited by Hans-Michael Koetzle of “Leica – Augen Auf ” fame. It has texts by Sabine Hock, Randy Kaufman, Hans-Michael Koetzle, Kristina Lemke, Günter Osterloh, Tobias Picard, Gerald Piffl, Shun Uchibayashi, and Thomas Wiegand. It is a hardcover book of ca. 464 pages, with ca. 600 color und 300 Duplex images. The book states as its purpose that it is: “the first comprehensive book on Wolff and Tritschler [that] recapitulates the work and careers of both photographers against the backdrop of a politically, socially, and artistically turbulent period and thus closes a gap in the discourse on photography in the 1920s to 1940s”. The book is readily available, often at a discount, at the time of this writing.

Disclosure: This reviewer had a discussion of books titles from his own work with Mr. Kaufman regarding his new bibliography here, and a philosophical and historical dialogue with Ms. Lemke about Wolff and the Nazi’s after she made her contribution to the volume, but otherwise no input into this publication.

Upon receipt of Mr. Koetzle’s book, the first impression was how BIG it is. This is not so much its physical size by coffee table book standards but rather the scope of its subject mat- ter. When Cyril and this reviewer started our bibliography, we really had no idea how very large the material was going to prove to be, and here we have not only the small corner of Wolffiana that we looked at, but everything Wolff and Tritschler were involved with. Their career coincided with the technology explosion of the middle third of the 20th Century (airplanes, automobiles, and the Leica camera), political turmoil of a major degree, popular culture, movies, radio, picture magazines, the Bauhaus movement, and so on. Wolff and Tritschler became Germany’s foremost photographers of their era with the largest output of any of their colleagues. However, by 1950 their reputations had dimmed.

Part of the salient yet ambiguous backdrop to Wolff and Tritschler careers has been, and continues to be, the degree of their relationship with the Nazi regime. It has long been the reviewer’s opinion that this rather heated question has both held back real discussion and appreciation of Dr. Wolff ’s work, and yet will basically never be fully answerable. Even someone known to this reviewer whose family was close to Dr. Wolff during the 1930’s recently asked for my opinion about this; he himself apparently had no comfortable answer from what he had been told, and was as much conflicted about the available evidence – or lack thereof — as anyone else.

A previously unpublished factory shot from the Niehues & Ditting cloth making concern. A playful and striking image.

Dr. Wolff chose, to the degree he had a choice, to remain in Germany during the Nazi period and work at his profession. So did the Leitz family for their business, and while they were dutifully otherwise producing cameras and other optical items for the Wehrmacht, they made hidden heroic efforts to help Jews and others. We know only belatedly of these actions. While it is doubtful that Dr. Wolff did anything remotely as heroic as this himself, there is no information other than the most circumstantial of evidence what the degree of his willing cooperation with the regime may have been, or how he viewed things. Such evidence as exists cannot take into consideration what he might have been forced to write or include by the censors to get his books published, or what Nazi conventions he needed to conform to in order to remain in business. We do know that the U.S. Army administration hired Dr. Wolff for his work fairly immediately after the war, at least by mid- 1946, (circumstantially) showing that it did not consider him a political risk. We know fairly conclusively that Dr. Wolff was never a Party member. We also know that Nazi ideas and tropes are at times present in Dr. Wolff ’s books and speeches, that some of his images were used or repurposed as propaganda, and that Dr. Wolff belonged to a few Nazi-sponsored profes- sional associations. Kristina Lemke’s chapter in Koetzle’s book offers a reasonable and balanced assessment of this topic. It is interesting that some other well-known photographers of the period had definite Nazi connections, yet were not pilloried for collusion the way that Wolff was posthumously. Lemke says in summary (p. 356): “Everybody who remained in Germany and wanted to work without harassment was under obligation to comply with the authorities’ orders. During a time when daily life was politically influenced in all areas, an unpolitical demeanor was impossible. Wolff ‘s images deferred to the visual vocabulary and culture of the period, and had a share in their development at the same time. As an arbiter of photography, Wolff was unique—both before and during National Socialism”. Adding to this: Wolff and Tritschler’s vision of “lively photography” was indeed new and unique. This vision was partly a biproduct of the then-new Leica camera’s ability to render things in such a manner, and the compelling new images lent themselves readily to propa- ganda purposes, for good or for ill. The famous image from the 1936 Olympics of Jesse Owens and German athlete Luz Long – close up, tightly cropped, and visually powerful as only a 35mm camera coupled with Dr. Wolff ’s vision could have made it – illustrates such propaganda possibilities and ambiguities.

Due to the growing popularity of the Leica camera and Wolff ’s didactic books about it, he had readers not only in Germany, but in England, Japan, and the United States as well in the early 1930’s. Then the Nazi era and the War cut them off from all but local appreciation for many years.

There are likely several reasons other than their location in Nazi Germany why this famous pair lost their notoriety after the War. Wolff and Tritschler employed a variety of photo- graphic styles, and while much of it involved portraying the homeland sympathetically, there is modernism similar to several schools of aesthetics to be found in their work. But their photography, while easily recognizable, is not that eas- ily classifiable and therefore not subject to certain people’s collecting tastes or desires. Further, Wolff and Tritschler focused on and were among the first to publish industrial photographs, mostly for anniversary books, and the majority of these were published in fairly small, private editions.

Actual prints – art prints especially – from the duo are not that common, and indeed such was not what concerned them commercially: rather, they made books and ran a stock agency for the publishing trade. As a result, almost all renowned Wolff and Tritschler images reside in books, magazines, or ephemera, and most of these were published only in Germany owing to the political circumstances of their times. In addition, all of Dr. Wolff ’s early glass plate negatives were destroyed in the War.

Finally, photography had moved on to more obviously provocative subject matter-less “lively” and more personal or documentary — around the time of Dr. Wolff ’s death in 1951. To a degree then, Wolff ’s vision seemed old fashioned at that point. And what Wolff and Tritschler had done with their labors popularizing the Leica format and making it user friendly was gradually subsumed into the common shared knowledge base among photographers, so that by 1970 it barely registered as innovative.

Koetzle’s book attempts to do what all of us who revere Wolff ’s work have also struggled to do: to remedy the decline in the reputations of Wolff and Tritschler; to “close a gap” with discussions on their place in photo history and the nature and importance of their output; and in general to bring them back within the canon of great photographers.

Wall placard from the Leitz Museum exhibition which accompanied this book. Wolff is quoted, with an English-language translation that appears to minimize the vehemence of Wolff ’s feelings. Note that when Wolff says he had not “learned” photography, he meant that he was self-taught and therefore felt he was not being taken seriously. His learned profession was medicine.

Examining the book itself, the chapters are filled with many images by Wolff and Tritschler, not always fully relevant to the adjacent texts perhaps, but almost dazzling in how they immerse the reader in the Wolffian aesthetic of “lively photography”. Mr. Koetzle contributes a long and interesting chapter on Dr. Wolff ’s history from boyhood on, including his relationships with publishers and with his partner Tritschler, how his firm operated, and his focus on such subjects as adver- tising, periodicals, and books for industry. Paul Wolff ’s life story is, by necessity of a lack of source material, somewhat conjectural and incomplete at points, open to differing interpretations, and more than occasionally enigmatic. There is not only the question of Wolff ’s involvement, or not, with the NSDAP, as above. There are the difficult issues of his leaving Alsace after WWI and relocating to Frankfurt, not having medicine readily available to him as a profession, and his fairly prolonged attempts once there to develop his career as a photographer. These issues appear to have taken a psychological toll on Wolff, and it is not clear if Wolff ’s behavior later in his career — in his needs for fame, financial security (Wolff charged an almost- outrageous amount for his work), and control over his subjects – are causally related to these difficulties. The Leitz Park Gallery show had on the wall Wolff ’s own words about this period, taken from an autobiographical sketch published in 1935: “Immer wieder versuchte man, mir Knüppel zwischen die Beine zu werfen”. Translated roughly into English, this would be something like “Again and again people tried to trip me up” or perhaps “they always tried to throw a monkey wrench into the works”. [See the image from the exhibition and its benign English translation]. If Wolff actually felt this way concretely rather than just using colorful language, then he might be viewed as having what we today call “anger issues”. And a stance like this may have affected his basic outlook on the world as well, not to mention how he related to his employees, his publishers, his photo subjects, or his family. Wolff treated his close associate Tritschler rather oddly and subordinately, and the consensus has been that they were not really friends. He also had two failed marriages, a mental breakdown after his home and glass negative collection was destroyed in the War, and a drug problem near the end of his life. Possible chronic unhappiness and character issues would have seemed foreign to the avuncular persona he presented to the world in his writings, and would have needed to be kept private – and so on. We just don’t know the details. But despite such caveats, this is a very useful chapter to get to know the man, and it contains infor- mation which was new to this reviewer, some of it quoted from third parties who knew Wolff. In a good summariz- ing paragraph, Koetzle states (p. 90): “In Paul Wolff ‘s own eyes, he was liter- ally a guide and a teacher when it came to the Leica. In respect of the industry, he was an apolitical service provider, capable of documenting the manufac- ture of felt cloth and the production of armaments with equal ease and flair. He was also a contact partner to an illustrated press that looked beyond the day’s current images for its optical fodder. An artist he was not, which did not prevent him and employee Alfred Tritschler from even reconstructing the dictates of a New Vision again and again…”

A plate camera illustration of forks, circa 1927. This shows Wolff ’s playful “lively” photography, even before he turned more exclusively to the Leica.

This chapter is followed by one on Wolff ’s photography of the city of Frankfurt, written by Sabine Hock. Covered are Wolff arrival in Frankfurt and his attempts to get employment there, his associations with several individuals who helped him, most no- tably historian and city promoter Fried Lübbecke, and his portrayals through the years of both the medieval and new city with both plate camera and Leica. Wolff ’s many books on Frankfurt are also discussed and illustrated.

Following this are two chapters about Wolff and the Leica camera, the first again by Koetzle, recounting first the story of Dr. Wolff ’s first Leica, allegedly won at a competition, his actual belated use of the Leica (starting only in 1927 in earnest), and then his relationship with the Leitz company and the many books that he published which benefited both parties. Typical of the enigmatic issues with Dr. Wolff raised here, no one can find evidence of his winning a Leica, even though Wolff, and later his first wife, stood by this story rather vehemently. Wolff had known Oskar Barnack and his work since 1921 (or 1923, depending on what one reads) and there are two Model I(a) Leicas marked for delivery to Wolff in the 1926 Leitz shipping ledgers, so the prize story, if apocryphal, was really not necessary except for Wolff ’s self- narrative. Again, typically confusing are differing shadings about the degree of Tritschler’s influence upon Wolff in his choosing the Leica and on their working relationship. Enigmatic also is the difficulty of actually establishing the size of enlargements which Wolff and Leitz exhibited worldwide in 1933/ 34 in their show “Meine Erfahrungen mit der Leica”; one would have thought, wrongly it turns out, that this would be easy to discover.

The second chapter centering on the Leica is written by Leica historian Günter Osterloh and covers much about the early Leica system that will be familiar to LHSA, organized around the difficulties Wolff and others had coming to terms with its early limitations.

Image from 1936 Olympic Games: Jesse Owens and Luz Long (from Wolff ’s Olympic books)

Following is a chapter on Dr. Wolff ’s reception in Japan, by Shun Uchi- bayashi. Here we learn of the interest in Wolff ’s fresh new manner of photog- raphy and the excitement at his Leica exhibitions and several books just for the Japanese home market, followed once war started by an attempt to use Wolff ’s books as propaganda. Japan was probably second only to Germany as a country where Wolff was esteemed and appreciated in the 1930’s.

Next up is a presentation by Thomas Wiegand of the backbone of Wolff and Tritschler’s business: the indus- trial photographs and books. Covered here are the authors, designers, and publishers with whom Wolff usually

worked, the difficulties of publication under the regime, especially into the war years, and Wolff ’s often prima donna-ish behavior to get his way with recalcitrant company officers, who wanted only traditional overviews of their work halls. “According to all my inclinations, I am not the man of the static image, but of the animated picture plucked out of reality. After all, the fact that I see things differently, and in a lively way as well, than factory photographers do, for example, has made me famous and brought me many enthusiasts… I can only adhere to reality, and cut out of this reality the ‘part that represents the whole,’ the quintessential feature that I recognize after many decades of practice… I still believe that it is more valuable to live a little bit dangerously …than to sit at a desk, smoking a pipe, and philosophizing over ‘amateur complexes’. That way we are of no use at all to the next generation of our profession.” (pp 293-4) Once again in this chapter there are many well-chosen examples of these publications.

Following Kristina Lemke’s writings on Wolff and the Nazi regime, cited earlier, we get an interesting short chapter by Gerald Piffl on what can be gleaned from the back side of Wolff & Tritschler prints. More than just origin and copyright reside here in 1930 prints sent out for publication. There may be a brief often handwritten synopsis of the title and reason for the shot, and stamps relating to where the photo has resided, or in the later 1930’s a government censorship notice, directing return of the image once it had been used. In this reviewer’s own work on the Wolff photos used by Photographia zu Wetzlar, such stamps offered information about how that enterprise organized and sold its offerings.

Finally, we get a valedictory chapter on Wolff in Frankfurt during and after the War by Tobias Picard. Picard’s chapter is a quite well-documented history, a blow-by-blow account of Wolff ’s activities – both solo and as requested by Hitler – to document Frankfurt before its likely destruction by the Allies, then of Wolff ’s depression when his home and much of his collection was destroyed in a bombing raid, and finally of Wolff ’s mostly futile attempt to regain his status until a combination of ill health and economic / social realities made this impossible. There are many color images here, few of which this reviewer had seen previously.

At the end of the book there is a year-by-year summary of historical happenings in Wolff ’s life – which includes biographical information not otherwise presented in the chapters – and bibliographies by book category of the Wolff/ Wolff & Tritschler books by Randy Kaufman, and of other Wolff materials by Mr. Koetzle. These expand upon this reviewer’s own bibliographic work, and add a new category to it, respectively. Reference notes and an index follow.

———————-

Impressions of this book: As mentioned at the start, the subject of the book – Wolff and Tritschler – is huge, yet deceptively manageable. What we are given here is a bird’s eye overview of a gigantic landscape, with descent into several areas of interest in various chapters for a closer look. Interspersed are images of books and their contents, many of the duo’s iconic images, and bibliographical information.

In 2015 this reviewer pulled together bibliographical, biographical, and historical / analytical material on Dr. Wolff and finally published an arbitrarily-limited annotated Wolff bibliography. From the book’s back cover blurb: “the author decided to find and collect the totality of Dr. Wolff ’s photo books, little appreciating at the time that this quest would take him over 20 years. Along the way, he had to immerse himself in 1920’s and 1930’s German history, bone up more specifically on the history of the Leica camera and the E. Leitz company, and cultivate relationships with historians and anti- quarians”. What Mr. Koetzle and his crew have done here, with obvious enthusiasm and affection one should add, is to try to take this quest up another notch. Have they succeeded? The answer for this reviewer is: both mostly yes and somewhat no. There is much more fascinating detail available from their researches than ever before, and in places the picture of Wolff in his milieu is clearer than what has been put forth previous- ly. The many images, some seen essentially for the first time, are intriguing and often beautiful. Picard’s chapter succeeds best in this dimension, owing to good source material and a circumscribed subject matter.

The downside is that the Wolffian landscape becomes increas- ingly complex the closer we get to it. It is an inside joke among Wolff bibliographers that while one can currently publish a spiffy bibliography, new and unknown Wolff titles will con- tinue to turn up ad infinitum, such that we can never get a complete list, a catalog raisonné if you will. Similarly, as a much needed first approximation to the full Dr. Paul Wolff and Tritschler story, this book has succeeded quite well, but important data is likely lurking in the shadows and will need to be found and brought forward. There are still the enigmatic issues raised earlier regarding several key points in Wolff ’s history, and more generally the task of trying to understand

the elusive man behind the photographer. Wolff ’s autobiog- raphy, written in 1950, is quoted many times in the book, but has never been published; one wishes this would happen so that others could work with it. It may be noteworthy also that Wolff ’s descendants do not figure here with any biographical material or images they might possess. So, there is likely more, perhaps much more, to know.

Koetzle’s book also, likely of necessity, has a discontinuous quality as several scholars all try to add bits and pieces to the story, to understand Wolff ’s complex character, motivations, and full output. Thus, the book has about it the aspect of an anniversary volume or Festschrift rather than the single-mindedness of a monograph by one or two scholars. A chronicle with more obsessive detailing and continuity will be required at the next levels of this mighty endeavor. But overall, as a Wolff researcher, this reviewer applauds the effort here and would not want to be without this book; it is recommended highly to our membership.

Just as in 1999, it is with hope for the future that this reviewer considers the rich endeavor here, Koetzle’s book, to be part of an ongoing “Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler Studies” program. One expects there will be more to come.